More Intermittent Fasting

...and its role in cardiovascular health (read all the way to the end!)

There are many neurotransmitters (NT) in the human brain. These are chemical messengers between nerve cells (aka neurons). You are probably familiar with the NTs dopamine (from its well-known role in reward, though that’s a complicated story) and serotonin (from its well-known role in depression, another complex picture). Neuroscientists are still discovering new NTs.

The two most prevalent, and in my mind, important NTs in the brain are glutamate and GABA (I won’t stress you with its full name). Glutamate is what’s called an excitatory NT. In other words, it activates neurons and is required for activity in the brain. Without it your brain wouldn’t be doing much at all. Too much, or uncontrolled, activity of the neurons that produce glutamate, can cause epileptic seizures, for example.

GABA is what’s called an inhibitory NT. It’s the balancer to glutamate. Think of these two as up and down volume controls. Glutamate is spread throughout the brain by the neurons that produce it. GABA acts more locally; by slowing or reducing glutamate production it puts a lid on brain activity.

For example, when it starts getting dark outside, some of the information traveling from the eyes to the brain gets routed to the pineal gland where melatonin is produced. You may be familiar with melatonin’s role in promoting sleep. In this role, it activates some GABA-releasing areas to start shutting down overall brain activity, leading in to sleep. (This is a very over-simplified picture of sleep initiation!)

Let’s tie intermittent fasting into brain activity now.

For a fuller discussion of intermittent fasting, listen to the NIH scientist who developed the idea (he also has written a book on the topic).

Scientists used to think – way back when I was in graduate school – that once we were born we didn’t develop any new neurons. Life was one big progressive loss of neurons. We now know that is not true. Like in all other organs there is a reservoir of ‘stem cells’. These are ‘immature’ cells, that can be called on to start growing up into a mature specialized cell. Maybe a stem cell could take a route to become a GABA producer or a glutamate producer, or some other kind of neuron.

We know that in some brain regions, for example the hippocampus, a brain area very important in formation and storage of our memories, that stem cells can form new neurons in response to exercise. In other words, exercising can improve our ability to learn and remember. Intermittent fasting has the same result. Put the two together and you get a better result (at least in mice) than either alone. On the other side of the coin, disease states, like diabetes, can result in the loss of hippocampal neurons.

How could this work? Well, it’s really difficult to try to answer this question in people so researchers usually turn to animals. In this story, one researcher grew rat neurons in the lab in different conditions. In one set of petri plates (shallow round dishes with a nutritious gelatin layer that allows cells to grow) she put a high level of glucose, mimicking a typical feeding pattern where blood sugar is elevated through the day. In a second condition, she added a type of ketone, which is the compound our cells use when stored fat is broken down for energy, as occurs during fasting when blood sugar levels are low.

The ‘fasted’ cells increased their output of an important chemical called BDNF (if you really want to know, this stands for brain-derived neurotrophic factor), which in general acts to protect neurons and stimulate their ability to make connections with other neurons. Encouraging neurons to up their production of BDNF means healthier, longer-lived neurons that can participate in more cross talk in the brain. Exercise also ramps up BDNF production.

BDNF has different effects, depending on the brain region. It’s pretty safe to say that increasing BDNF output in any area will have a protective or optimizing effect. Let’s go back to the role of GABA. Remember that this is an inhibitory NT, which tones down brain, and nervous system, activity.

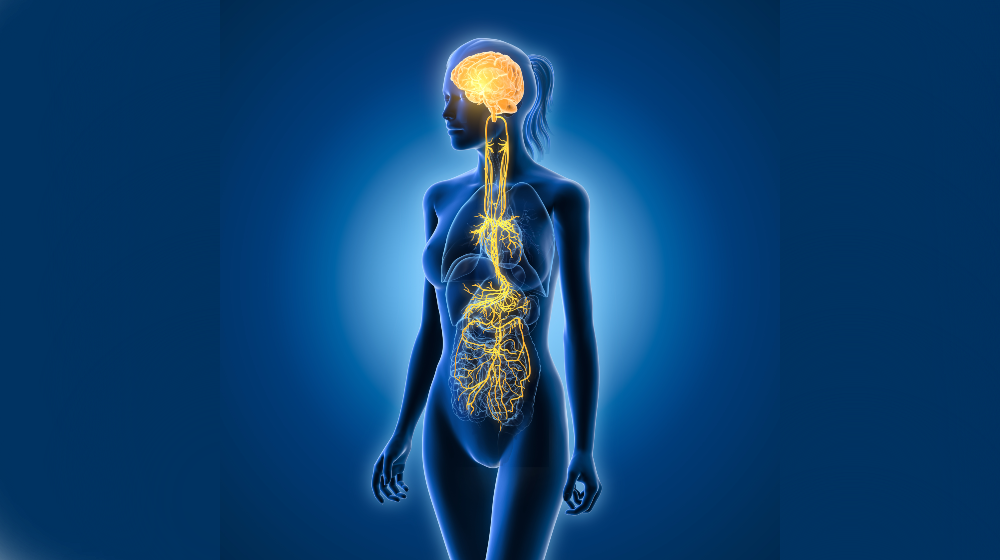

One part of the nervous system where GABA plays a really important role is the parasympathetic nervous system. You may be familiar with what is called the fight or flight response. This is a system-wide response to perceived threats, resulting in activation and readiness to, well, fight or flee. There is a big chunk of your nervous system dedicated to these actions like fight or flight, that you don’t have to control consciously. This portion of the nervous system, called the autonomic nervous system, consists of portions of the brain just above the spinal cord, and nerves there which run into the rest of the body. There are two opposing parts of the autonomic nervous system; one, controlling fight or flight, is the sympathetic system. By now you may have guessed that the parasympathetic system is the balancing act, cleverly termed ‘rest and digest’ for its ability to counter the activation of the sympathetic branch.

Now we can go back to GABA by way of the vagus nerve. This is the major nerve of the autonomic system, and the longest nerve in the body. It starts out in the lower regions of the brain, and reaches to the lungs, heart, and gut, among other destinations. (Vagus comes from the Latin word for wanderer, and this nerve, and its branches, do wander around the thorax and abdomen.)

Activity of GABA-producing neurons in the vagus nerve calms the many organs that it reaches. Think of slowing your breathing, or heart rate, after being alarmed by some external stressor, such as a driver suddenly cutting you off, terrifying you in traffic. Perhaps counter-intuitively, a low level of sympathetic arousal occurs during exercise. The action of the parasympathetic system in recovering from these stresses is really important in maintaining cardiovascular health.

If you want to dive more deeply into the vagus nerve, this geeky neuroanatomy video will get you started. You can appreciate the many body locations it reaches, and also that information flows both to these organs (the ‘efferent’ path that the narrator describes) and back to the brain (the ‘afferent’ pathways). You may also be aware that there is a huge and diverse field of good research and (IMHO) wild speculation on how to engage the vagus nerve for a plethora of effects ranging from sleep to weight loss to addiction and trauma recovery.

Enter the fasting story. (And don’t forget exercise too.) These two activities directly calm and optimize a bunch of heart and lung functions by their role(s) in increasing BDNF output, and thereby optimizing GABA levels, in the vagus nerve.

And post script: as I was posting this, I saw a new study, not peer-reviewed (i.e. not subjected to the usual pre-publication critique of the typical scientific study), claiming that IF increases risk of heart disease. But, the devil is in the details, and this particular study suffers from a lot of those- so don’t dismiss IF!

Hi Beth, I thought of you on reading this article in the NYTimes this am

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/25/world/europe/italy-aging-valter-longo.html?ugrp=u&unlocked_article_code=1.fU0.QeAO.kZ6bLzYmonno&smid=url-share

Thanks for this piece Beth. I have been interested in BDNF and GABA for a while now and taking steps to improve, like exercise, nutrition and supplements but I will take a look at the video as well. I know that IF works miracles for lots of things.