Alzheimer's Disease

Part 1: The Basics of the Disease and Treatments

We have all noticed that age-related changes in cognition (i.e. broadly speaking, one’s ability to learn and process information) are extremely variable. One person can recite long poems from memory or solve difficult mathematical problems at 95 years of age, another will develop dementia at age 50.

I’ve been thinking a lot about dementia lately. My mom had some type of undiagnosed dementia the last few years of her life, perhaps Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form. According to the CDC, almost 6 million Americans were living with this disease in 2020. My former lab director and aging researcher, Tom Johnson, was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia about five years ago. Parkinson’s disease, which affects some 2% of Americans, can progress to dementia. Most of us have family members or friends with or who have had some type of dementia.

Dementia is an umbrella term encompassing any type of cognitive decline. I’ve already defined cognition, and if you’ve been reading my posts, you are now all-too-familiar with age-related declines. There are a lot of reasons for this drop off in mental ability, including overall health, education, socioeconomic status, and genetics. It’s encouraging to note that in most healthy older people cognitive abilities don’t decline much. In fact, the wisdom of accrued experience increases, and we can continue to learn new skills throughout life.

Age-related changes in the brain have been studied for over two centuries but we still can’t say much about what constitutes ‘normal’ change. Much of the uncertainty is due to the difficulty of examining a brain in a living person. Recent advances in technology, such as the MRI, are changing this. The most obvious change is in brain weight, which is pretty stable until about midlife, then, like so many other physical features of the body, begins to decline. Brain volume, which correlates well with weight, drops 0.1–0.2% a year from 30–50 years, then falls off the cliff to 0.3–0.5% a year after the age of 70.

Scientists used to think that we lost more and more neurons (i.e. the brain cells that communicate with one another to produce thoughts and control our bodies) as we aged. More recent studies found that, in general, neuron loss with age is either undetectable or relatively mild. Once you pass 80 years though, all bets are off. After 80, neurons are lost due to the processes that sometimes result in Alzheimer’s Disease, the focus of this and the next few posts. Neurons are also affected by cerebrovascular disease (i.e. damage to blood vessels), which of course, is also more common with age.

Almost everyone experiences some declines in memory and motor performance with age, some of which is normal with age, because of the loss of neurons. In other words, we will all experience age-related changes in our brains where the extreme end point is neurodegenerative disease – but most people don’t live long enough to get there!

Unlike other chronic illnesses, such as heart disease and cancer, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is becoming more common in our aging population. Recent estimates suggest that AD has become the third leading cause of death in those over 65 in the United States after coronary disease and cancer. It’s not surprising that many of us are concerned about it.

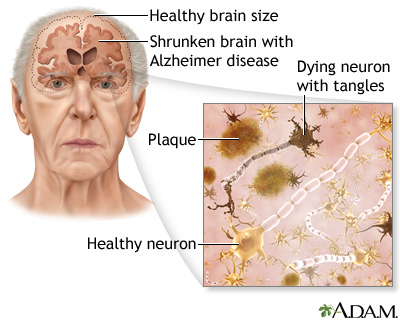

Specifically, AD is a ‘progressive neurodegenerative disease’ characterized by accumulation of abnormal proteins, resulting in so-called plaques and tangles Plaques are globs of protein that accumulate between neurons in the brain. Amyloid plaques are a hallmark of AD. Amyloid is a general term for protein fragments that the body produces normally. Beta amyloid, the type associated with AD, is a piece snipped from a specific protein found in the cell membrane of neurons. In a healthy brain, these protein fragments are broken down and eliminated. In AD the fragments accumulate to form the hard, undigested chunks we call plaques. People with AD typically have a lot of these plaques, though people without the disease may have them too. Many researchers think that large amounts of the plaque are toxic, thereby damaging neurons, but it’s a hotly debated topic.

‘Neurofibrillary tangles’ are globs of protein that accumulate inside neurons. In AD, the tangles consist primarily of a protein called tau. Normally, tau functions to transport nutrients and other important substances from one part of the nerve cell to another. In AD, the tau protein has become abnormal and it eventually breaks down, causing the tangles to form. Of course, the normal function of tau is also lost, meaning that the neuron slowly starves. The end of the neuron that talks to other neurons, is the first to go. As a result, affected neurons can’t talk to other cells and brain circuits start to break down. (For a good visual on these things watch the youtube video.)

Youtube:

Perhaps the first event in the origin of many dementias is impaired circulation to the brain. When you consider that neurons are large, metabolically active cells, the importance of good blood flow to the brain is obvious. The brain, which accounts for less than 5% of body weight (much less in some cases!), uses almost 25% of the body’s energy budget. A reduction in cerebral blood flow reduces the clearance of the plaque protein, beta amyloid, which then can build up to high levels in the brain of AD sufferers.

The reduced blood flow is relatively easy to detect, and may be a good early diagnostic tool for AD. So what you say, why bother with a diagnosis. For one thing, if you know you are at risk for developing AD, you can start implementing some of the lifestyle changes I will come back to in a subsequent post. One main player seems to be a type of blood cell called a white blood cell, that sticks to capillary walls, gumming up these little vessels. In mice that were genetically altered to have AD, treatment with an antibody that prevented the white blood cells from sticking to the capillaries, restored blood flow. Like humans, these mice had lost memory but this was restored by the antibody treatment, even in really old mice with in advanced stages of Alzheimer's disease.

We also get more iron accumulating in the brain as we age. Why? No one really knows. Iron is an essential component of many enzymes in the brain but high concentrations of reactive iron can contribute to oxidation damage. I’ll return to this point later also.

To recap, the causes of dementias are many, and not well understood. A few genes are known to contribute to early onset of the disease, sometimes as early as the 40s. Fortunately, those are rare. Lifestyle can also contribute; both as cause and protection, as I suggested above in noting that vascular disease can worsen the buildup of plaques. The effects of lifestyle and how we can tweak them to stave off dementia are the subject of the next post.

Finally, despite years of research, no really effective drug treatments have emerged. In fact, of the thousands of drugs tested in this effort, less than 1% have been approved by the FDA. There are three currently marketed for early, moderate AD. These are all drugs, called cholinesterase inhibitors, that block the action of an enzyme that breaks down a neurotransmitter (NT), called acetylcholine.

No one understands why inhibiting the enzyme, which prolongs the action of the NT, works to reduce the symptoms of dementia. One hypothesis is that acetylcholine is an important NT in the communication pathways among brain regions involved in attention, memory, and cognitive activity. Inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine can improve memory, as well as helping people with AD or dementia from Parkinsons’s to remain independent and retain their personality. It seems to be more effective in people with a more aggressive form of their dementia, e.g. those with younger onset ages, poor nutritional status, or experiencing symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations.

A more recent drug targeting the beta amyloid (recall this is the main component of plaque) was approved amidst a lot of controversy by the FDA. It too shows only small effect and only in people with mild symptoms and in the early stages of the disease. Its price tag (upwards of $65000 per year), and Medicare’s refusal to pay for it make it generally unavailable.

The mitigating effects of both drugs and lifestyle depend on early diagnosis. To date, the only truly accurate diagnosis is based on autopsy. Clearly not especially useful in early detection. There are some promising tests on the horizon. These include PET scans (images of the brain looking at activity in certain regions), CSF measures (cerebrospinal fluid; which may contain amyloid beta), and blood tests (some markers in the blood may correlate and thus predict brain levels of amyloid, or other damaging compounds).

One thing we can all do at an early stage is to get a baseline cognitive assessment. Some of these must be administered by a psychologist or neurologist, but others are available online. Much like a baseline colonoscopy or mammogram, this test provides a standard of comparison against which later symptoms can be evaluated.